The Canton Trade and Hong Merchants

"The system devised by the Chinese for carrying on the foreign trade was a masterpiece of wisdom. In no part of the world could operations of such magnitude be carried on with so much ease. The only merchants allowed to do business with foreigners were the Hong merchants."

— John Heard referring to the hong merchants, from his diary, 1891

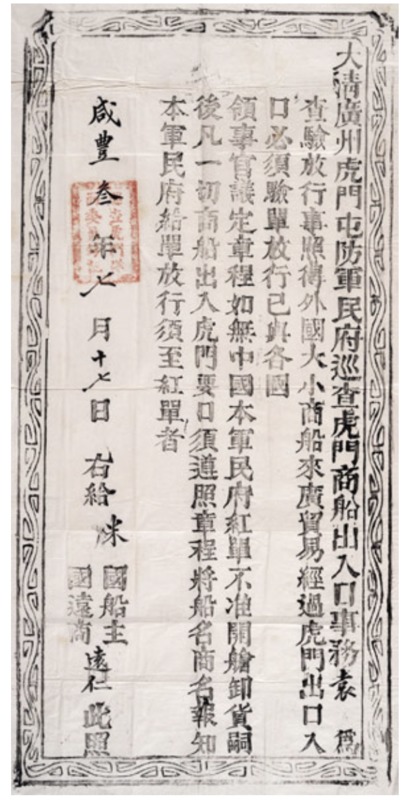

A Hong (Chinese: 行; pinyin: háng) originally designates both a type of building and a type of Chinese merchant intermediary in Guangzhou (also now known as Canton), Guangdong, China, in the 18-19th century, specifically during the Canton System period.

The name hong originally referred to the row of factories built outside of the city walls of Guangzhou (Canton), near the Pearl River. The Thirteen Factories were used during the Canton System period to host foreign traders and the products purchased, under the aegis of the cohong. The Hong (or Factories) were usually owned by hong merchants such as Pan Zhencheng.

The Guangzhou Hong changed location several times after fires, and became less important after the First Opium War (1839–1842), as Guangzhou lost its monopoly of foreign trade and Hong Kong was ceded to the British as a colony.

During the period known as the Canton trade system (1757–1842), hong merchants acted as exclusive liaisons between American traders and the Chinese. Holding the license to trade issued by the Chinese government, the hong merchants enjoyed considerable power. All foreign trade was required to be channeled through them. They purchased most of the imports, arranged for exports back to America, and made sure Westerners followed customs and duty regulations. Samuel Shaw, an American consul in Canton, described the hong merchants as “intelligent, exact accountants, punctual to their engagements . . . [who] value themselves much upon maintaining a fair character. The concurrent testimony of all the Europeans justifies this remark.”

The hong merchant Houqua came from a family of privilege. He eventually amassed his own fortune as well, and his wealth hovered at $26 million, making him not only one of the richest hong merchants, but also among the richest men in the world. Other Chinese worked their way up through the system, from hired laborers to clerks to hong merchants, making personal fortunes through sales with Western traders

The hong merchants cultivated close relationships with Western traders like Augustine Heard and provided them with valuable guidance. “[Houqua’s] great success was at least due in part to his friendship with the Boston clan . . . but the Bostonians owed [Houqua] at least as much. Not only did he aid every family representative who came to China, he continued to favor some long after they returned home,” Jacques Downs notes. These familiar connections benefitted individual merchants as well as the relations between the two countries. “I am very glad to see America and China on such good and friendly terms,” Houqua wrote to Boston trader John Murray Forbes in 1842.